In a calm yet confident reply, the Assam Chief Minister busts myths around China’s control of the Brahmaputra, reminding the world that the river belongs to the rains, the land, and the people of India, not political scare tactics.

Terming as baseless and motivated by misinformation the recent assertion by a Pakistani government minister that China could halt the flow of the Brahmaputra River into India, Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma has categorically rejected the fear as unfounded and part of fear-mongering. The Pakistani remark, which was seemingly an attempt to create hysteria over India’s water security, elicited a caustic reaction from Sarma, who pointed out the geographical and hydrological realities of the Brahmaputra.

The controversy started when Rana Ihsaan Afzal, Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s Coordinator on Commerce and Industry, suggested that China might retaliate against India’s recent actions regarding the Indus Waters Treaty by stopping the flow of the Brahmaputra River into India. The proposal was made as a rhetorical threat of the consequences of politicizing water resources but also evidenced ignorance of the river’s source, volume, and dynamics.

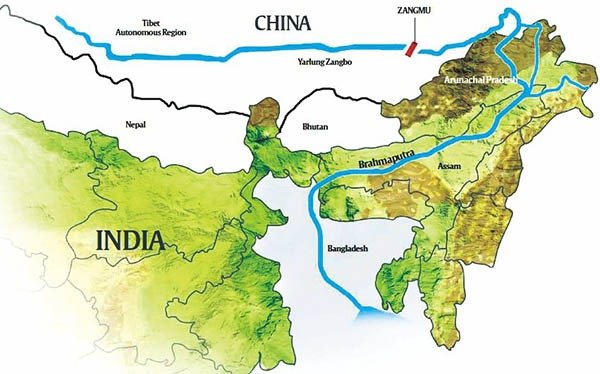

Sarma replied on social media by offering a detailed description of the structure and flow pattern of the Brahmaputra River. He said that unlike Pakistani officials’ claims, the Brahmaputra is not mainly reliant on water from China. Actually, he mentioned that merely 30 to 35 percent of the river’s overall flow is contributed from the Chinese segment (where it has been named Yarlung Tsangpo), and the rest 65 to 70 percent is contributed within Indian territory.

The Chief Minister expressed, “Most of the Brahmaputra’s water is contributed by rain in Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, and other Northeast Indian states.” Furthermore, the river has numerous tributaries, Subansiri, Lohit, Kameng, Manas, Dhansiri, Jia-Bharali, which contribute substantially to its volume once it moves into India.” He said that the river in fact bulges hugely after it crosses the Indian border, more so during the monsoon months, when the flow actually increases from about 2,000–3,000 cubic meters per second along the Indo-China border to more than 15,000–20,000 cubic meters per second downstream in Assam.

Sarma also spoke of the possible fallout from any attempt by China to cut down the flow of the river. “Even if China were to cut down water flow from its side, which I find highly doubtful, it could actually benefit Assam by lessening the flood impact we endure every year. Thousands of people are displaced and lose out every monsoon season due to the flooded Brahmaputra,” he said. The statement was viewed as a pragmatic and assertive declaration of India’s water security and resilience.

This whole conversation is in the context of larger water diplomacy realignment in South Asia. India has recently put on hold the Indus Waters Treaty, a several-decades-old water-sharing arrangement with Pakistan facilitated by the World Bank, on grounds of persistent provocations and necessity to revisit historic concessions. The step was taken in the wake of the terror strike in Pahalgam, Kashmir, for which India had accused Pakistan-based groups. The treaty has been criticized by Prime Minister Narendra Modi as a “badly negotiated” agreement that most favored Pakistan, and the government has indicated its desire to make the fullest possible use of India’s share of the Indus waters for which it is entitled.

Pakistan’s counter-narrative, which posits that China could strike back at India by blocking the Brahmaputra, seems to be a move to instill a perception of geopolitical encirclement and water vulnerability. Nevertheless, Sarma’s fact-based debunking has successfully shattered this narrative.

Water researchers and political observers have pointed out that China is not likely to take such a drastic step as stopping the flow of the Brahmaputra. Any move to control river flow unilaterally would not only attract international legal repercussions but also damage China’s image as a responsible upper riparian nation. Further, hydro-engineering schemes on such huge transboundary rivers usually encounter practical, environmental, and diplomatic challenges.

Assam, which is in the Brahmaputra’s lower basin, is especially prone to floods annually. As a result, Sarma’s comment also demonstrates a greater sense of appreciation for the area’s longstanding issue with water management. His observation highlights the point that instead of being concerned about speculative upstream diversions, India should continue to focus on building infrastructure and water management systems for flood-proofing and harnessing its abundant water resources more efficiently.

Finally, the Assam Chief Minister’s assertive yet educative reply has gone a long way in putting to rest baseless apprehensions regarding India’s water security, particularly in the northeastern region. By pointing out the hydrological facts of the Brahmaputra and laying bare the emptiness of Pakistan’s hypothetical threat, Sarma has asserted India’s sovereignty and readiness with regard to the management of one of its most critical natural resources. His message to the general public and geopolitical observers alike is unmistakable: India is not merely well-informed but also well-equipped to manage internal problems and external efforts at destabilization in the form of misinformation.